Amid criticism that law schools are graduating too many lawyers for not enough jobs, three Missouri universities will admit fewer students this fall.

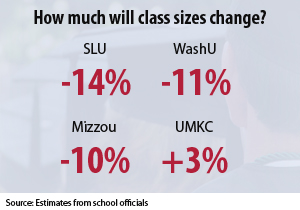

Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Missouri and Saint Louis University are planning to admit about 10 to 15 percent fewer law students than last year, at a cost of millions of dollars in future tuition revenue.

The reduction in class sizes comes as all four Missouri law schools report even larger drops in the numbers of applicants.

Smaller classes may address legal industry concerns and also could bump up schools’ U.S. News & World Report rankings because of factors such as expenditures-per-student and student-to-faculty ratio. But school officials say they have other reasons in mind.

Officials at the University of Missouri School of Law chose to reduce the incoming class size by 10 percent this year. At 135, the entering class hasn’t been this small since it has been housed at Hulston Hall starting in 1989, said Michelle Heck, director of MU law school admissions.

Washington University in St. Louis School of Law will decrease its incoming class size by 9 to 13 percent, said Janet Bolin, the law school’s associate dean for admissions and student services.

Officials at Saint Louis University School of Law plan for a 13 to 15 percent drop in its class size of part-time and full-time students this fall, according to figures from Michael Kolnik, assistant dean for admissions.

At the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law, the entering class size may be a little larger, with about four more students this fall than last year, said Ellen Suni, dean of the law school.

Suni said the school’s class size was based on, among a number of factors, keeping a constant student body population. She said the first-year class will vary depending on the continuing size of the second- and third-year classes as well as LL.M. students. UMKC’s law school is not trying to increase its overall student body enrollment, she said.

Applications for this fall’s entering class dropped by 16.7 percent at MU; 12.3 percent at WashU; 19.7 percent at SLU; and 8.7 percent at UMKC.

School officials said they believe there are fewer applications because the entering class has had more time to research law school amid well-documented industry turmoil. They also point out that application numbers are cyclical and have periods of growth and decline.

Another factor could be rising tuition. An average student considering enrolling in law school now should expect to graduate with more than $100,000 in debt.

At MU, Dean Larry Dessem said the law school dropped its class size not only to “right size” the student body with employment trends, but also to also provide better hands-on law experience, which is more difficult with a larger student body.

He said the school is reducing its class size as a matter of choice and not necessity.

“Clearly there has been a measureable drop in the number of legal positions, and we want to be able to focus on a smaller group of students to best prepare them,” he said.

The smaller class size also may help the school’s ranking — which has fallen 42 spots to No. 107 in the last two years — because data such as the average per-student expenditure will improve, Dessem said. Still, he said, that wasn’t the ultimate aim of having fewer students.

As for any concerns about fewer people applying to the law school, he said, “we are clearly concerned when we see an impact on the quality of students in the classroom, but I don’t foresee that for us.”

At Washington University, the law school wanted classes to be a little less crowded, Bolin said. This will improve faculty-to-student ratio, but this wasn’t the main goal, she said.

“From a teaching perspective, you get to know your students better when there are fewer students,” she said.

But with fewer applications, she said, it’s more challenging to obtain a highly diverse class. “You may not have as much variety,” she said.

Saint Louis University also wanted to keep student enrollment at a constant level. The previous two incoming classes have been large, and school officials wanted to reduce the entering class size, Kolnik said.

He said it wasn’t a decision the school made based on employment data, but that consideration could apply in future years.

Industry turmoil

There’s plenty of bad news lately to deter law school hopefuls.

Nationwide, there’s a surplus of more than 27,000 lawyers, according to an analysis by Economic Modeling Specialists Inc., or EMSI. Missouri ranks 10th in a list of states where the number of new lawyers exceeds the number of lawyer job openings.

While 943 people passed Missouri’s bar exam in 2009, the state has about 362 lawyer job openings annually, leaving a surplus of 581 lawyers, according to the EMSI data.

New York was ranked the highest, with 7,687 extra lawyers. Wisconsin and Nebraska were the lowest-ranked states; they have shortages of lawyers. EMSI, based in Idaho, collects data on the labor market for analysis of employment trends.

Meanwhile, law school placement news continues to get gloomier. Last month, the Association for Legal Career Professionals, or NALP, reported that the employment rate for 2010 law school graduates, at 87.6 percent, is the lowest it has been since 1996.

The organization measured the employment rate of graduates as of Feb. 15, 2011, which is nine months after a typical May graduation.

For graduates whose employment was known, only 68.4 percent were in jobs that required passing the bar — the lowest percentage NALP has ever measured. Also, fewer graduates had jobs in law firms — 50.9 compared with 55.9 for the class of 2009.

Just a couple of weeks ago, NALP also reported that the national median salary for 2010 law graduates was $63,000, a drop of 13 percent from the class of 2009.

The salaries fell because graduates found fewer jobs with high-paying law firms and more jobs with smaller law firms, which typically pay the lowest starting salaries, said NALP executive director James Leipold in a statement.

Total enrollment

Other schools also have decided to drop class sizes. For example, Albany Law School and Touro Law Center in New York plan to admit fewer students this fall, according to the New York Law Journal.

Brian Tamanaha, a Washington University law professor who is writing a book that examines the economic structure of law schools, applauds schools that reduce enrollment.

“The question is, why are they doing it? They’re smart to do it, but this isn’t [solely] of out of altruism. Because if they don’t do it,” he said, “they may suffer a decline in LSAT median” scores when there are fewer applications.

Schools that drop enrollment can make up for it by, for example, cutting research opportunities and reducing discretionary spending, Tamanaha said, adding these are difficult decisions.

Despite some individual schools that have decided to reduce enrollment at one point or another, Tamanaha pointed out that total enrollment among all law schools has risen.

Total school enrollment for students seeking law degrees increased to about 145,000 in 2009 from 127,000 in 1990, according to statistics from the American Bar Association.

Tamanaha said schools have bulked up with more faculty overtime, making it harder to decrease their revenue by decreasing the number of students they enroll. It’s difficult to trim faculty because professors can have long-term contracts and tenure, he said.

Faculty compensation and expenses typically make up half or more of schools’ annual budgets, he said.